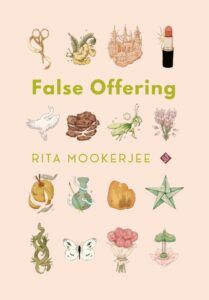

Reading: Dr. Rita Mookerjee’s new poetry collection, False Offering

Liberal and Interdisciplinary Studies Assistant Professor Rita Mookerjee’s first full-length collection of poetry, False Offering, published by JackLeg Press in Nov. 2023, addresses topics ranging from religion to pop culture staples to being a person of color growing up in a rural part of Pennsylvania. Mookerjee has studied African literature, post-colonial literature, women’s and gender studies, and food studies. Her next collection of poems, Banana Heart, will be published in the fall.

Staff writer Rebecca Cross sat down with her to talk about the book.

Liberal and Interdisciplinary Studies Assistant Professor Rita Mookerjee

Q: When did you start writing poetry?

A: 2001. The first poem I ever wrote was a spoken-word poem. I wrote it when I was 11 because I was very angry that my parents would not let me go to the mall without an adult. [She laughs.]

Since then, poetry is where I go when I don’t have a place to put something I’m feeling, whether that’s rage or irritation or frustration. Poetry is definitely the place that I prefer to go when I have those big, capital-F feelings.

Q: The title poem, “False Offering,” describes ancient Egyptian priests selling fake ibis mummies to unsuspecting penitents. What was the inspiration behind this?

A: When I learned about this, I was so mystified because you’re traveling all this way through the Necropolis to get this offering, and then you just end up with a mummy that’s this weird chimera bundle of random animals. There was just an obscenity to it that I was very taken with.

Yesterday, I was looking at a politician’s Twitter page, and he was posting pictures of their morning prayer, and I was immediately reminded of the book of Matthew and how it’s very clear in scripture, you’re not supposed to be bragging about how much you pray.

I think “False Offering” is about taking inventory of why you’re practicing a faith and considering, if all of the bandages fall away and it turns out that you didn’t really have what you thought you had in the first place, where does that leave you?

Q: A number of your poems are inhabited by Hindu, Judeo-Christian, Haitian, and ancient Egyptian deities. Where did this interest in religion come from?

A: While my parents definitely did the best that they could in terms of giving us important cultural experiences and explaining to us different faiths, different practices of religion, the amount of exposure I had as a young person was very limited. There was never a space that we would go to to either pray or observe a holiday or give offerings or anything like that.

As a result, I think the entire process of worship and the rituals became very mystifying to me. I’d been to Sunday school or to synagogue with a friend, and I could understand why people enjoyed that or why people found solace in those spaces. But at the same time, I just didn’t get it. Like, to me, it was just a huge inconvenience because I was like, Jen and I are over here having a slumber party, and now she has to get up and go to Sunday school.

I’ve now read the Bible many times as a scholar of literature, and I think there are a lot of really beautiful teachings, but when I was a kid growing up, all of it was so confusing to me. And I think what was most confusing was the hypocrisy. Like, people would say, you can’t do x, y, or z or you’re going to hell. And I’d be like, okay, but it also says you can’t mix cloth, and there are certain foods you need to eat at certain times.

There are so many rules, and you’re only choosing some of them. Why is that? And today, I know why. But as a child, I was very disturbed by the disconnect that I saw between these things.

Q: You mention “white space” in a couple of different poems, like “Infestation” and “I Grew Eyes at the Nape of My Neck.” What is the significance of that in your poetry?

A: If you live in a super rural area, there’s probably some likelihood that you’re not going to have a ton of diversity in your community. That’s where I was growing up. It occurred to me several times when I was in elementary school that it didn’t matter if I sat quietly and did a good job and paid attention. It didn’t matter if I goofed off and spoke back to my teacher, which I did a lot. It just didn’t matter because everything about the world that I was in wasn’t for me, and it wasn’t going to be kind to me or supportive of me. And so I tried to find a lot of pathways out of that rural space—quite literally. I moved to New York when I was 18. Even then, when I got my master’s, when I got my doctorate, time and time again, I would find myself in these situations where people wanted me to have a certain identity and a certain set of politics that I just don’t have.

And even when, say, well-intentioned white readers might come to my events or my talks, sometimes they’re still coming in with this very specific expectation for what someone who looks like me is going to say and think and do. Most of the time I can navigate it, but it is exhausting because it seems to happen more often than not. Another expectation of that white space that I find suffocating is people really want me to give them my American dream story, and they really want to hear a tale of poverty and suffering that ends with me, you know, joining the professoriate, and what a wonderful thing that is, and how grateful I am for those opportunities.

And the fact of the matter is, yeah, I love my job. There are a lot of things that I’m grateful for. And there are a lot of things that I’m mad about right now. So I think one of the expectations that people don’t have is that an Indian woman poet is going to be really militant and outspoken.

Q: Speaking of militant, the poem “A Man Threatens to Shoot Me on Behalf of ‘Infidels for Trump’” has some really great righteous anger. It talks about the Hindu goddess Kali, who wears a belt of severed male heads and then ends with the lines, “watch your neck because / I’ve got plenty of room on my belt for you.” What’s the story behind that poem?

Q: Speaking of militant, the poem “A Man Threatens to Shoot Me on Behalf of ‘Infidels for Trump’” has some really great righteous anger. It talks about the Hindu goddess Kali, who wears a belt of severed male heads and then ends with the lines, “watch your neck because / I’ve got plenty of room on my belt for you.” What’s the story behind that poem?

A: Like everything in that book, that’s something that happened in my life. I was single and online dating in Florida. Online dating wasn’t really something I had done before, and I was really struck by how many people on Tinder, Bumble, or what have you, would greet you with a slur or a sexual comment or just be rude.

I was really floored because I had in my bio very clearly what my politics are and what I do for a living and things like that. So I hoped that would be enough to dissuade people, but actually, what it did was encourage people who are bigoted and have a lot of hate to match with me and then send me these really violent, bizarre comments.

So this person matched with me and then sent basically a copy and paste with lots of gun emojis and stuff like that. All of this violent rhetoric about how, under Trump, he and his “infidel gang” were going to round up and kill people like me, and that it was their country, etcetera, etcetera. And I think my first response was to laugh because it was so heinous and unprompted. But the more I thought about it, the more upset I got because here I am just trying to have a nice little fun date on a Friday.

I don’t really remember people talking to one another that way before 2016. And so the poem, I think, is me trying to make sense of a cultural moment where either out of my own naivete and ignorance or out of the world genuinely changing, I’m trying to make sense in that poem of what to do when people are just cruel.

Q: You have several poems about icons of pop culture, like Sailor Moon and Tamagotchi.

A: One way that I tried to make sense of my world was with things I liked to do. Anime and cartoons were a big part of my world. I think I liked Japanese cartoons specifically because it felt like something that didn’t belong to all of these white people in my community. It wasn’t mine either, but it felt different enough that I could go to that space and look at drawings or creatures or monsters that were like nothing in the world around me, and that was comforting.

Q: The book has a sweet poem about your mother, “Portrait of Sujata Who Never Dresses Down.”

A: I think it took me 30 some years to understand what she was doing, and that’s why I really wanted to memorialize her in that poem. Because when I was growing up, I was embarrassed. I was like, why is she putting on all this jewelry and lipstick and getting all ready to go to the grocery store? That’s not what so and so’s mom wears to the grocery store, and I felt very self conscious about it. And now today, I do that same thing myself. If I want to be treated properly, I’ll go in dressed to the nines. A lot of women of color I’ve spoken to as I’ve gotten older have shared that exact experience.

Q: The collection has several other tender poems about your family: “Rooh Afza,” about your father, and a poignant poem about your sister, “Hard Water.”

A: With “Hard Water,” my sister is getting sick. We are seven years apart, and we’re very close. The thing with bipolar disorder is that it doesn’t present in children. You really start to see the symptoms in adulthood. Even then, because it’s not a lateral set of symptoms and experiences, it’s not easy to diagnose. There were a lot of times near the time of her hospitalization where I just didn’t know what was going on with her. I wasn’t hearing from her. There was so much confusion for me as her older sister and as someone who had always been the one that she comes to with problems or comes to with a dilemma or needs advice. Suddenly there was a thing in her world that I couldn’t advise her on. I was in so much pain because it was my favorite person in the world suffering, and suffering in a way that I couldn’t do anything to limit that suffering or help take on some of the burden of that.

I’m happy to say that my sister has come a long way since I wrote that poem. And she’s very open about her struggles with her health, and I think, not to speak for her, but I think something that she wants is for people to find that poem and be able to put words to what they’re going through and what they’re experiencing. The sooner you can name it, the sooner you can ask for help.

In immigrant communities and communities of color, mental health is just seen as this western import. So, I think I really wanted to break a silence and let other people know, you’re not alone.

Q: A number of the poems are about rural Pennsylvania, where you grew up. I wanted to ask you about “If I Could Rename My Town, I’d Call It Lost,” which starts with the lines, “It was something like Dorothy in reverse, clicking my heels / in quiet desperation, willing myself to an emerald city // because the place where I grew up is cursed.”

A: Yeah. I think something that doesn’t occur to people sometimes is how diametrically opposed a lot of our experiences are as Americans. Like, despite the fact that we live in the same country and maybe we do a lot of things the same way, depending on where you live, you can have a really wildly different experience.

While I wasn’t necessarily someone who experienced poverty, I lived in an impoverished place. I was going to school and seeing how some of my classmates didn’t have clean clothes. No one packed them a lunch. Maybe they wouldn’t have sneakers for gym class. Things like that, that I certainly didn’t think twice about. I didn’t realize or appreciate it until much later, but there were people right there in front of me, experiencing hardships that no child should ever have to experience.

And now when I go back to my town, I see it’s just been ravaged. We, as Americans, have a responsibility to speak out and advocate when we know there are communities that are suffering. Just thinking about the realities of young people right now who might be marginalized in some way or might be queer, growing up in places where there are already so many issues at hand and so many social problems, so many structural problems, we’re not setting them up for success. I have a lot of love for people who are from little middle-of-nowhere towns like myself because the odds are just not in your favor.

At the time that I wrote this poem, there were about 24 people in my graduating class who are dead. And now I’d say there’s about 36. And that’s a class of maybe 100 people. I mourn that people have to grow up in an area where you are so at risk for addiction, or not having the resources you need to be well, or not being able to recover from an injury or take time off work, things like that.

It’s not an elegy in title, but I think it is an elegy.

Q: Another poem that stood out to me was “Shoes in My House: An Allegory,” which describes an episode where a friend visiting your house refuses to take off her shoes. Now, I’m definitely a shoes-off-in-the-house sort of person, so I immediately was like, ‘Oh, that friend is so rude!’ But this poem isn’t about just a rude friend; it’s about that white space.

A: Oh, absolutely. I think that’s why it was so abrasive to me. In Asian households, there are important reasons why we’re asking you to take off your shoes. Whereas in the household of my white friend who wouldn’t take off her boots, she doesn’t have a cultural reason why she’s wearing her boots.

My home is very sacred to me, so when I invite someone into that space, I’m not saying you need to thank me on bent knee, but it is a gift. I’m going to feed you, and we’re going to have a nice little time. And then the refusal to respect the way that I like my house and the way that I like people to be in my house, it just felt cruel and selfish in this really specific way. Kind of like the Tinder moment with the Trump supporter, it was just a record scratch moment for me. I couldn’t wrap my head around why someone would be so unkind.

Q: I’m a big fan of the killer, knock-you-out last line. I really loved the ending of “This Is Not a Form of Play,” which is really almost an ode to opossums: “I find you lucky / enjoying night as it was meant to be enjoyed […] / thriving in places where people forget to look / people forget so much.”

A: Oh, I’m so glad you like that. Yeah, I feel like even I neglect that poem sometimes because I don’t know how to explain it to people. Like, I just really love opossums. They’re so smart and clever. And, I think they’re so neglected and underappreciated. The fact that they can remember, ‘Oh, I had a really good egg over here.’ I find that so charming.

Q: Another line that really knocked me out was in “Hamsapaksha, or the Swan’s Wing Mudra”: “the skin I call my own is streaked with danger.” And this is another poem that has some of that righteous anger.

A: Yeah. That poem was more of a sad day. I was thinking about, on the one hand, I always tell my students, “power in numbers” and “they can’t kill us all.” Like, fight, fight, fight. But at the same time, there’s something so exhausting about constantly fighting and constantly trying to make a case for your existence.

In the ending of that poem, you just get that image of the swans descending. And people don’t know that swans can be very violent. We don’t think of them that way, but they can be. So I wanted to have that ominous swan imagery.

Q: How do you approach writing a poem?

A: Definitely by using a physical notebook and a pen, which I only say because now that’s unusual in the field. I don’t know a ton of other writers who really lean on a physical notebook. In that draft, I just get concepts out. Maybe I’ll know, ‘Okay, this is gonna be a sestina. This is definitely going to be a sonnet.’ But I don’t hold myself to anything necessarily when I’m just writing on the page. I usually want to preserve an image or something like that.

After I have that written draft, I’ll probably take that to the computer, and that’s when I’ll start to carve out a shape. I’m very particular in poetic traditions and forms that I will use for myself. I like symmetry. I like shorter lines, and I don’t mind committing to a longer poem or a very long series. That draft is usually when I’ll pay attention to sound and form, enjambment, and things like that. So at that point, I’ll have a good sense of, do I want to get some more eyes on this, or do I want to put it in a completely different form? Then I’ll go from there.

Q: Were there any poems in this collection that were particularly easy to write or particularly difficult to write?

A: There are some that definitely took me several tries to achieve what I wanted. Definitely the first poem in the book. That’s one of the last poems I wrote for this collection. I had a very specific shape in mind. I wanted it to read like an assembly guide or something, and getting that shape right with the sonic qualities that I wanted, that was pretty hard.

“False Offering” was super easy to write. It’s like a one-sitting poem. Sometimes, when I nail it, I really nail it. Other times, I have to revisit a lot. My tankas take time for sure because there’s a lot of counting. I have to be extra careful to make sure I’m not messing up my syllables because I’m a stickler about certain forms.

“Lesson from the Oracle Who Had Seen Too Much” was really hard. That poem originally looked very different, but when you’re formatting for printing the book, my long lines were just insane, and there was no way they were going to fit. So I had to kind of chop that poem up and give it another shape to inhabit.

Q: What is it about writing in forms, as opposed to free verse, that you find so appealing?

A: I’m interested in how something looks on the page just as much as I am in giving a killer performance. Anytime you encounter my work, I want it to be dazzling. I have a preference for really clean, deliberate shapes in poetry. That doesn’t mean symmetrical. It can be something like the sawtooth edge, which my partner, the poet Dorothy Chan, does a lot. It has this cool, wiggly property, but it’s still very controlled just like the teeth of a reel saw. I think there’s an aversion to form right now that I don’t think is earned. Like, if you study a lot of classical music, and then you decide jazz is actually what you like best, you’ve already really refined your craft, and now you can improvise confidently because you know all these fundamentals.

In poetry, I feel like all these poets hate form and talk about how it’s limiting or it’s too neo-colonial to use, but I think that’s a political act in and of itself. It’s like I’m writing in forms that these dead British men would have never been comfortable with me using, and I think that’s kind of cool.

I see so many poets not want to embrace form, but they never worked in form in the first place. I think learning is a lifetime process. When I picture myself in the writing trajectory of my life, I think I’m just getting started.