A Proud First-Gen History

Since 1874, Worcester State has provided an economic stepping stone for those who are first in their families to attend college.

The idea of “first-generation” or “first-gen” college students is a modern construct of higher education—but Worcester State’s history of inclusion and opportunity is a long and storied one that goes back to its founding.

From its early days as a teacher training school to its current status as an Emerging Hispanic Serving Institution, the university has always provided opportunities and support for students to achieve their dreams, regardless of their ethnic background or economic status, says university archivist and historian Ross Griffiths. As the city’s only public baccalaureate-granting institution, Worcester State has long recognized the importance of supporting students who were the first in their families to attend college.

Griffiths said information from the university archives, including a collection of handwritten tomes called the Statistical Registers, which contain information about students from 1874 to 1910, give a strong indication that many students were likely the first in their families to go to college. “The Register lists the types of occupations for parents, such as machinists, farmers, and housekeepers, indicating a working-class background for many students,” he said.

Over the decades, the ethnicity of first-generation students has become more diverse, as signified by the last names listed in campus directories such as the Register and in graduation lists. The shifts reflect successive waves of immigration to the area. In more recent years, the university has welcomed more students of Hispanic, Southeast Asian, and African ancestry.

“We don’t have demographic information other than names, but in the 1880s we see names like Collier, Clark, Cunningham, Grant, and Gates,” Griffiths said. “The names are very heavily Irish and English all the way through to the 19th century. In the 1890s, Italian names started to appear, and by the 1910s and 1920s, Armenian names became more common. A little later in the 20th century, there was an increase in Albanian, Greek, Syrian, and Lebanese names.”

Even as the ethnic make-up of the student body changed over time, the students’ working-class economic roots have remained, Griffiths said. “Worcester State has long offered a place for first-generation students who perhaps cannot afford enrollment at an elite institution, and the school has always worked to accommodate these students,” he said.

Some of those accommodations include flexibility in terms of class schedules, night classes, extension courses, summer classes, and a commuter-friendly campus that allows students who work full time to pursue their education. “This makes it easier for first-generation students, who may have work or family responsibilities, to attend college while still meeting their other obligations,” Griffiths said.

Worcester was an industrial town for a long time, and many students at Worcester State have had parents involved in manufacturing or trade professions, said Dr. Thomas Conroy, a historian and chair of the Urban Studies Department. These parents often had high school degrees or vocational training but rarely four-year college degrees. Worcester State, as a normal school, or teacher training college, offered a pathway for these students to gain a certificate and teach in public schools, which, for women, was among the few viable professional career options at the time.

“We’ve always had a lot of space for first-generation students,” Conroy said. “Worcester State has been a place where young women and men from working class backgrounds could come to get a well-rounded education and learn how to teach.”

The scope of Worcester State’s educational offerings has changed over the years, Conroy said. Once focused primarily on providing a direct pathway to a teaching job, the university became more comprehensive as new departments and programs, such as nursing, urban studies, and the arts, were created. This expansion of offerings reflected a shift in the mission to provide education and training for a wider range of careers, he said.

Over time, Worcester State expanded and began to focus on providing a well-rounded education, which appealed to students who wanted to learn beyond vocational skills, Conroy said. “By striking that balance, Worcester State has occupied an interesting space between a liberal arts college and a professional training school, making it attractive to working-class students seeking a practical education,” he said.

The university’s evolution continued after World War II, when there was an increase in first-generation students due to the GI Bill, and recently Worcester State was granted status as an Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institution with the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, which indicates a commitment to serving and supporting the Latino community.

“Worcester State has constantly evolved to meet the changing needs and demographics of its student body and the community,” Conroy said.

Worcester State’s Central Massachusetts location and relatively low tuition also offers first-generation students an opportunity to move up the social and economic ladder, Conroy said.

“We are centrally located, and that makes a difference for many of our students so they’re not traveling two hours to get to their classes,” he said. “In many instances we’re right in their neighborhoods, which makes it easier for the many families who have dreams of coming to the United States and being able to get an education, where they couldn’t have gotten that back home at an affordable price.”

This pragmatism and understanding of the needs of non-traditional students is in the DNA of Worcester State, he said, and the university’s focus on accessibility and meeting the needs of students from diverse backgrounds has contributed to its enduring appeal, particularly for first-generation students.

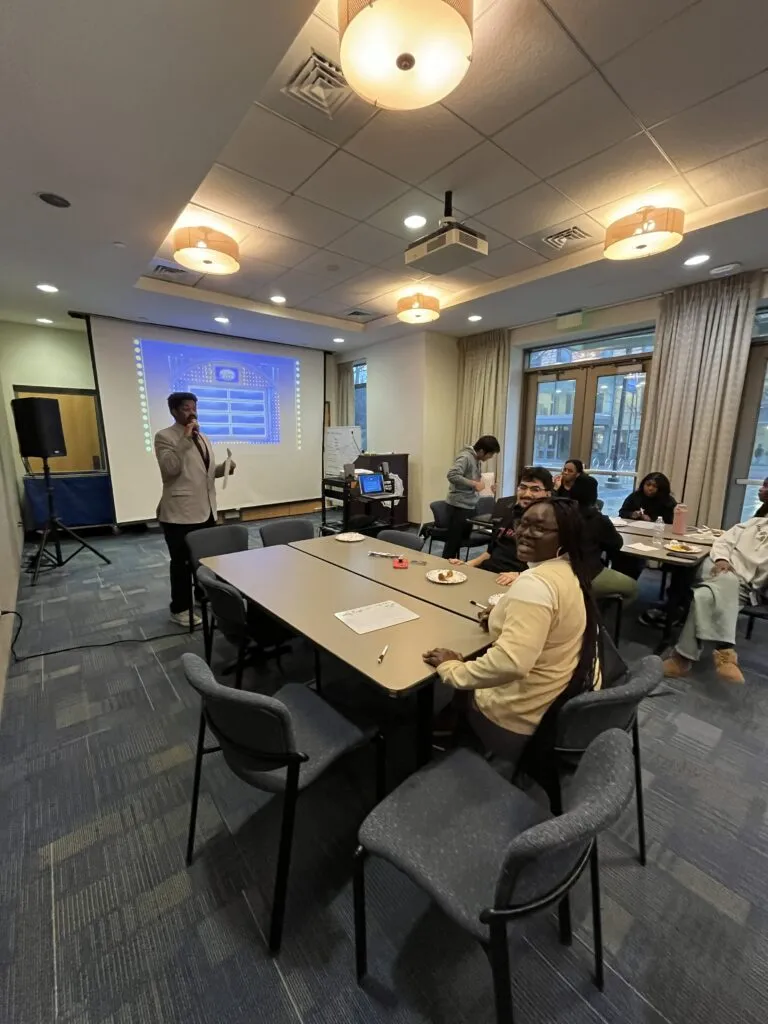

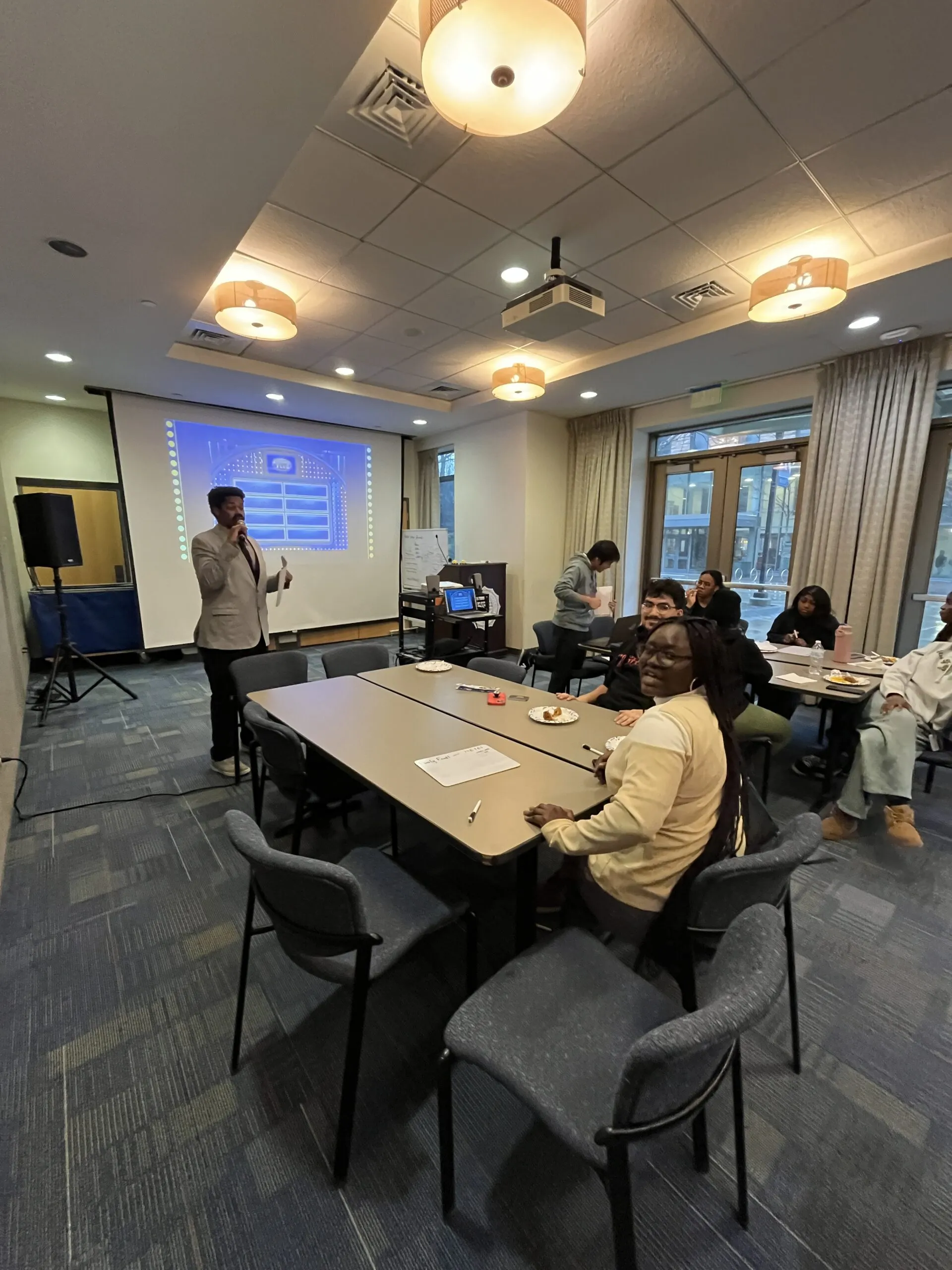

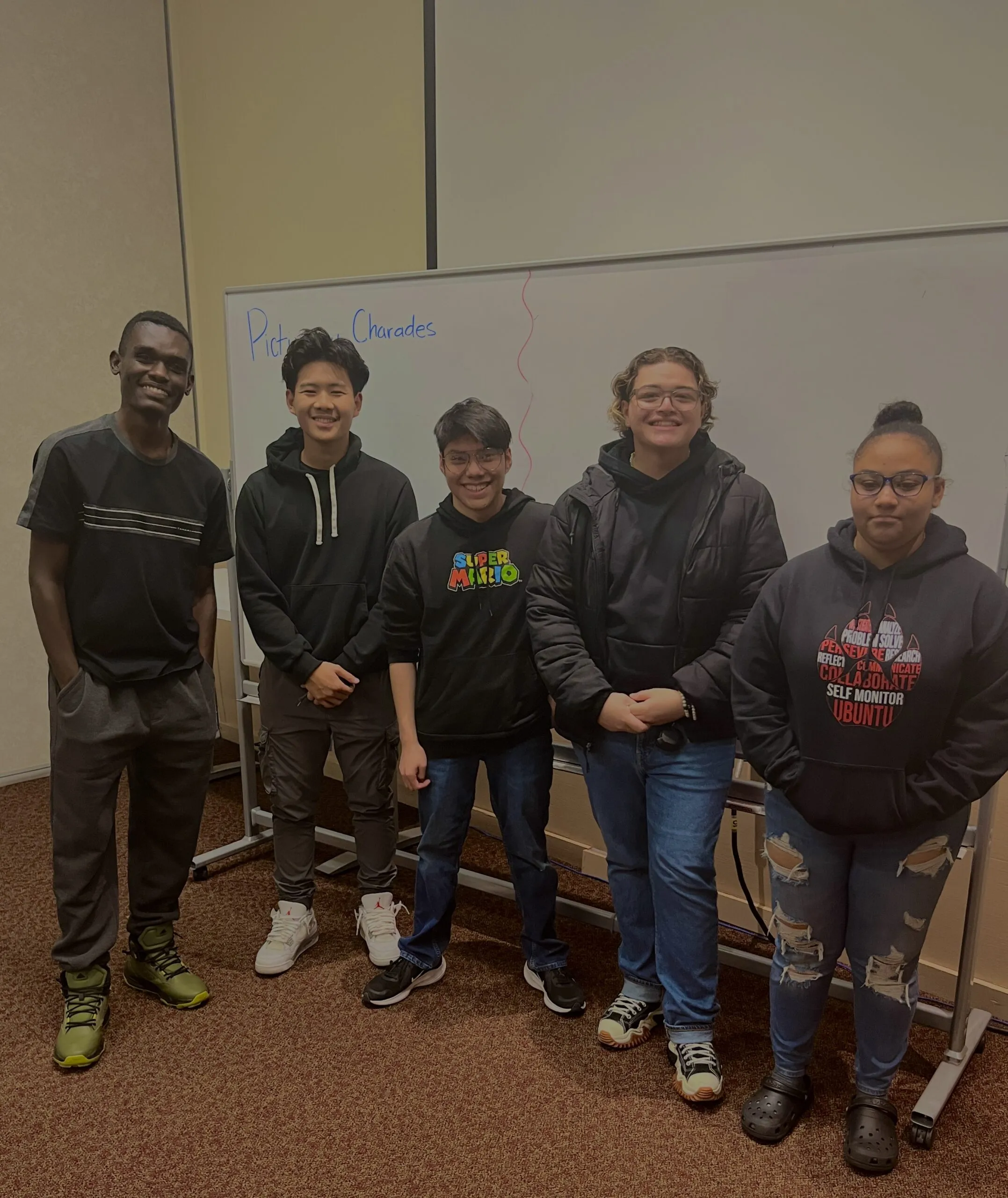

The university’s Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) has been central to supporting first-generation student success.

“Since its inception, Worcester State has been a magnet for first-generation students from throughout the area,” says Laxmi Bissoondial, the director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, who was herself a first-generation graduate of Worcester State. “In the more than 50 years since OMA was created, we have hosted several programs that have recruited, retained, and graduated first-generation, economically diverse students. Over the years, the demographics of the student body at Worcester State may continue to change, but we are excited to support the legacy of inclusion and academic excellence for all.”

By offering resources such as mentorship programs, academic support services, and financial aid, the university helps to level the playing field for students who may face additional challenges in navigating the college experience, Bissoondial said. This support can empower first-generation students to succeed academically and graduate.

“Mentorship is critical for these students, with peer-to-peer, faculty, and alumni mentors playing important roles in their success,” Bissoondial said. The university also focuses on addressing challenges such as financial aid, food insecurity, and mental health with a deep commitment to the goal of helping first-generation students graduate and become active citizens in their communities, she said.

As the 150th anniversary dawns, much about Worcester State has changed to keep up with the times, but the university’s most important aspects remain unchanged, Griffiths said.

“I really do think that institutions have something like personalities,” he said. “They have a life story, a biography that kind of manifests through the years. Even as administrators change and the mission changes and expands, at its core Worcester State still retains many of the qualities of the original normal school that was here for first-generation students—that well-rounded education, offering an economic stepping stone, meeting the needs of non-traditional students, that’s all still here.”

Top image: Worcester State Normal School students in January 1894, when the college offered women an opportunity to earn teaching credentials, one of the few professional careers available to women at the time.