Worcester State physicist returns to Nepal to tackle air pollution with Fulbright Award

Like much of Southeast Asia, Nepal is plagued by some of the globe’s worst air pollution, and it is causing serious health problems, from respiratory and cardiovascular damage to reproductive and gastrointestinal malfunctioning.

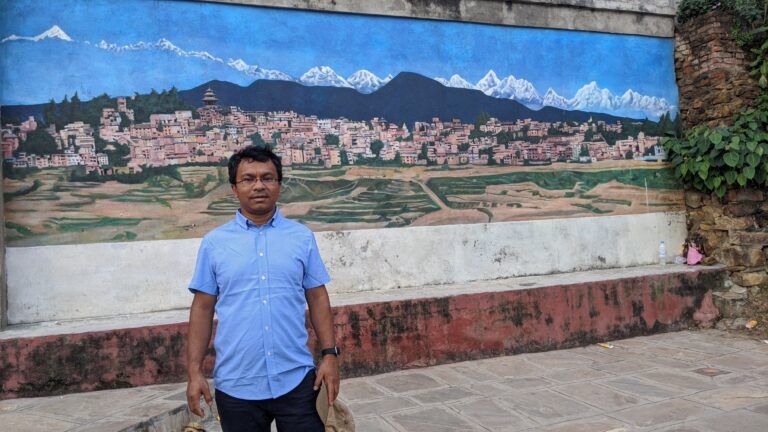

Worcester State physicist and air pollution expert Dr. Nabin Malakar, who was born in Nepal, has been tracking air pollution in Southeast Asia since 2011 using NASA’s satellite data sets. He has wanted to bring his expertise back home and work with Nepali scientists to tackle the problem. In the fall of 2023, Malakar got that opportunity when he received a prestigious Fulbright Specialist Award to spend the semester in Nepal collaborating with scientists at the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Sciences. Malakar said he was humbled and honored that Fulbright saw the potential of his work to make a difference.

data sets. He has wanted to bring his expertise back home and work with Nepali scientists to tackle the problem. In the fall of 2023, Malakar got that opportunity when he received a prestigious Fulbright Specialist Award to spend the semester in Nepal collaborating with scientists at the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Sciences. Malakar said he was humbled and honored that Fulbright saw the potential of his work to make a difference.

“This matter is near and dear to my heart,” said Malakar, an associate professor in the department of Earth, Environment, and Physics. “Sometimes you can see Kathmandu, Nepal, ranked among the world’s most polluted cities, which can be distressing, especially knowing the impact of breathing such polluted air on its inhabitants.”

Malakar is optimistic about effecting change, drawing on the success of air pollution policies in the U.S. that have previously demonstrated significant improvements. “Through the implementation of appropriate policies and putting them into action, it’s possible to see tangible results within our lifetimes,” he emphasized.

Air pollution in Nepal is driven by a combination of factors—transboundary pollution from neighboring countries, local fuel and cooking practices, industrial and vehicular emissions, forest fires, and meteorological activity. Overall pollution levels are about five times higher than recommended by the World Health Organization.

During his time in Nepal, Malakar was hosted by fellow scientists and friends Basant and Susma Giri, who founded the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Sciences. He worked with them and other colleagues at the institute to connect the satellite data sets with ground-level data that reveals just what people are inhaling. “There are not a lot of instruments to gather this ground-level data,” he said. “I wanted to close that gap by going on the ground and enabling people to collect the data.”

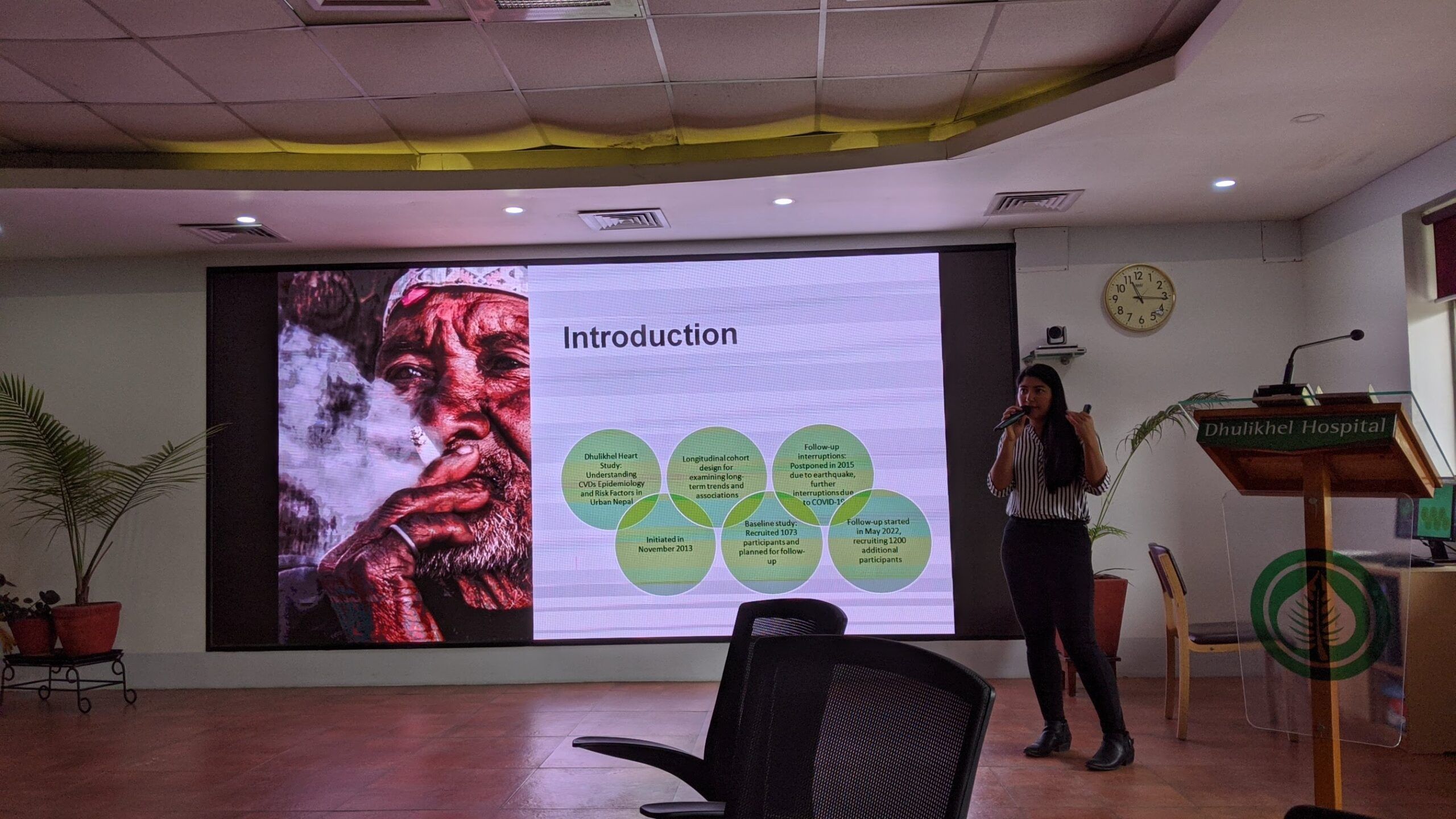

The group established two data collection stations in Dang Valley in midwest Nepal. Malakar trained 11 emerging scientists to use low-cost pollution sensors, remote sensing techniques, data analysis, model development, and public health communications. Malakar continues to meet with them remotely every week to review and analyze the data.

“It’s like going home to bring the knowledge you have to train the next generation of scientists, to affect the people impacted, and to contribute to policy change,” Malakar said. “You can say the air is polluted because you can see the dust and smoke. But you need to know how much pollution there is before you come up with mitigation plans and put any logical limits on emissions. Hopefully this helps policy makers make sense of the numbers.”

Malakar came to the U.S. in 2006 to earn a Ph.D. at SUNY Albany and did postgraduate research at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. His early work was in theoretical physics. Over time, he has expanded his focus to applied research and capacity building with the hope of making an impact on public policy to improve public health outcomes.

The World Health Organization describes air pollution as “a major threat to health and climate across the globe,” and a risk “for all-cause mortality as well as specific diseases.” Among the diseases linked to air pollution exposure: stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, pneumonia. There is also evidence linking air pollution exposure with increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, other cancers, diabetes, cognitive impairment, and neurological diseases.

Malakar hopes his work will engage the very people who are being impacted by the pollution.

“These people are dying early,” said Malakar. “You can avoid this damage to life and human health. This information gives power to the people. If they have the information, they can knock on the door and say, ‘I’m being affected by the ongoing situation, and urge you to take an action.’”

Scientific research on air pollution and advocacy for solutions has been underway in Nepal for years, said Malakar. “I’m just happy I’m one of the extra hands now available to hopefully change the way things happen,” he said. “This project resembles making a wish upon a tree, and in return, the tree grants you the wish—the ability to have a tangible impact.”

Photos courtesy of Dr. Nabin Malakar